If you catch a snippet of the radio in the morning on your way to work, you’re likely to hear what happened to the Dow Jones overnight.

If you read your news on-line or watch the news on TV it’s likely you’ll hear about the All Ords or maybe the ASX200. You might even come across acronyms like the NASDAQ and the FTSE.

Probably, you know this is something to do with share markets.

If you turn your mind to it a bit more, you probably know that the share market is where people buys and sell shares in companies like Telstra or BHP.

Maybe you have in mind that the share market is risky and people lose their money sometimes.

Well, if this is about the extent of your share market knowledge, you’re not alone, and this post is for you.

One avenue towards financial independence is to build wealth via investment in the share market. I should make it clear here that what I’m talking about is investing, not trading. If you’ve listened to the common investment mistakes series you will recall I covered off on the dangers of trying to be a share market trader. In short, it’s an almost guaranteed way to get poorer.

So we’re talking about investing. Buying shares that you intend to hold for at least a year, and profiting from both the dividend income, and growth in the value or price of the share over time.

There are different ways you can gain exposure to the share market. Your super fund likely has at least some exposure right now. Later I’ll look at a couple of options for your non-superannuation money, but let’s start by explaining a few of the terms and elements you will come across when you take an interest in investing the share market.

There a multiple markets

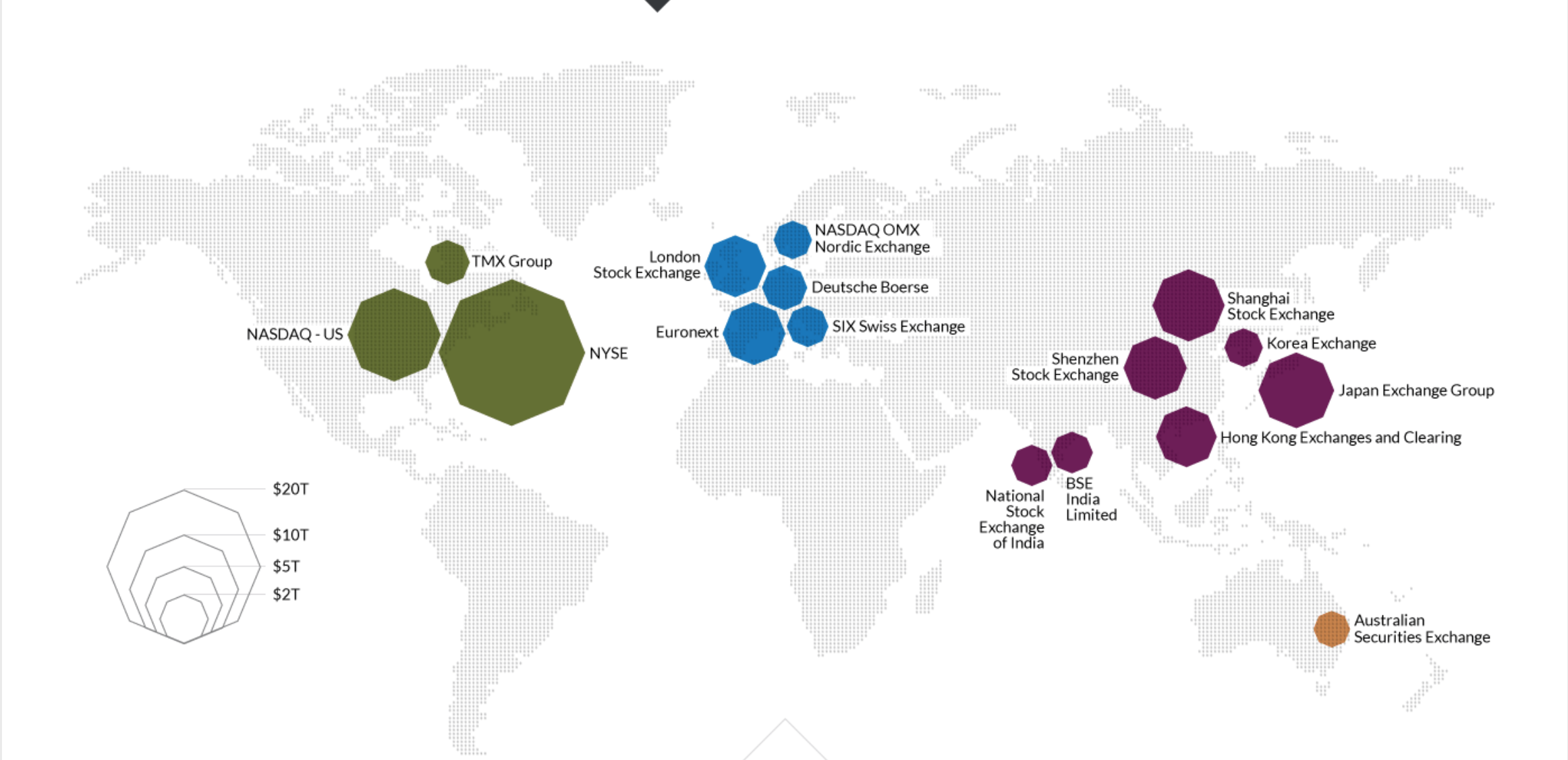

We refer to the share market like it’s one thing, but that’s not true. All developed countries have their own share market, and some such as the US have multiple markets.

There are 60 major stock markets around the world. There’s a good infographic on world share markets here.

Technology is gradually bringing these markets together in a practical sense for investors, but for the moment at least, as an Australian, if you want to buy shares in Apple let’s say, it’s not easy. Why? Because Apple isn’t listed on the Australian share market, and it’s not straight forward for an Australian investor to invest in the US share market (where Apple is listed) directly.

Our local market is called the ASX. The Australian Stock Exchange. Should be ASE really shouldn’t it, but presumably someone felt the X looked trendier.

On the ASX you’ll find lots of companies you’re familiar with – the banks, the big miners, Woolworths, Telstra, etc. Of course there’s also plenty there you’ve never heard of too. About 2,000 companies all up I believe.

In the United States the main market is the New York Stock Exchange. This is the largest share market in the world. On the NYSE you’ll find companies like Johnson & Johnson, Exxon Mobil, AT&T, VISA, and Pfizer.

The second largest share market in the world is also in the US – the Nasdaq. This market tends to be more technology focused, so Apple, Amazon and Microsoft are listed here.

There’s also the London Stock Exchange and on and on it goes – typically one per country.

You’re buying a piece of a company

The next thing to recognise is that when you buy a share, you are buying a small piece of a company.

Let’s say you buy a share in JB HiFi. You are now a part owner of that business. If that business performs well, you will get a share of the profits. If it grows and becomes worth more, the value of what you own will also rise. Of course if things go badly – maybe Amazon enters Australia and JB HiFi loses a whole lot of customers, then the business might decline, and so the value of your little piece of the company will do the same.

As a part owner you have the right to attend the company’s annual meeting and vote on issues like who should sit on the board of the company.

I sometimes have clients tell me that they prefer property investment to share market investment because they can touch a property. It’s a physical thing. They don’t feel that with shares.

Whilst I can understand that, if you think of the share you bought as a small piece of a company, then you can generally find something physical to attach to that. Walk into the JB HiFi store. You own a little bit of this.

Blue chip

If you start to take even a passing interest in share market investing you will soon come across the term “blue chip”. So what does it mean?

A blue chip share is a large, high value company. The expression is usually meant to infer that it’s a company that is so big it will never go broke. In Australia, the big 4 banks, BHP, RIO, Telstra, Woolworths, Wesfarmers – these are all businesses that would typically be described as blue chip.

There is no formal definition of a blue chip company, and you won’t see that as a descriptor on the ASX anywhere.

Interestingly, the term blue chip apparently comes from poker, where the most valuable chip was traditionally blue.

What to buy

So let’s say you’ve decided to dip your toe in the water and buy some shares. How do you decide what to buy? Well of course you could come to us for advice, but perhaps initially you just want to have a small go yourself to gain some experience – a great idea.

Some important numbers you might come across in your research are the dividend yield and the price earnings ratio. You’ll come across these numbers in the newspaper and on most share trading websites. So let’s take a quick look at what these mean.

Dividend yield – this is the income rate of return from the share and can be compared against bank interest rates to make it meaningful.

Resources companies such as BHP typically pay quite low dividend yields of around 2%, because they tend to pour a lot of their profits into expansion of the business, rather than paying out dividends. The banks on the other hand are more generous, usually paying 5-6%. And then there’s franking credits on top, but that’s for another day.

Price Earnings ratio – Commonly abbreviated to the PE, this is a ratio of the price of the share, divided by the earnings per share. So if company XYZ was trading at $10, and in its last earnings notice it declared earnings of $1 per share, then the PE would be 10. That is, its price is 10 times its earnings.

Most companies trade on PE’s of between 10 and 20 times. I find PE’s are most useful when comparing companies in the same industry, e.g. the banks, to see which banks the market is rating more highly than their peers.

A high PE often reflects an expectation that earnings will grow strongly in the future. In contrast a PE under 10 typically suggests that the market anticipates earnings will decline in future. As an investor you can consider whether you believe the market assessment is correct.

Importantly both these statistics relate to the share price on that day. If you already own the shares, and purchased them at some other price, it has no relevance, I guess unless you are thinking of selling.

It is also important when considering both of these measures to remember that the earnings numbers they are working off are historical, backward looking – nothing is certain in the future.

How else to get started with investing the share market

So you’re keen to invest, but don’t really want to get into the nitty gritty of choosing and monitoring shares yourself. Or maybe you’ve done a bit of that already and decided it wasn’t for you.

Fortunately for you, most investors who build wealth in the share market don’t personally do the research, buying and selling. As happens within your super fund, most people invest via a pooled fund where your money is combined with others and a process is used to spread your investment over many shares to reduce your risk.

The most common way to achieve this is through either a Managed Fund or an Exchange Traded Fund (ETF).

The difference between the two is that with a managed fund you apply to invest directly with the fund manager, quite possibly through an adviser. And when you want to take your money out, you similarly apply to the fund manager for a redemption.

Exchange Traded Funds however are bought and sold on the stock exchange. This means you can buy and sell more quickly, but it also means you will need to pay some brokerage to your stock broker each time you do so.

Another difference is that typically an Exchange Traded Fund is replicating a particular index, such as for instance the ASX200 – the largest 200 companies on the Australian Stock Exchange. The composition of the portfolio within an Exchange Traded Fund is therefore determined by some sort of mechanical, computerised type process.

Whilst some Managed Funds have this investment style too, more often Managed Funds will have a team of people doing research, and making buy and sell decisions based on this research. Within the industry this is known as Active investing, whereas the approach used by most ETF’s is Passive investing.

There is much debate within the investment industry as to whether Active or Passive approaches are best, and in my view each have their place. But an important thing for you to understand at this point is that ETF’s are usually cheaper than Managed Funds with respect to the management costs associated with running them, and this is because their process for selecting which shares to buy doesn’t require research and analysts.

The ETF market is growing increasingly popular, leading to considerable new product development. Given ETF’s are usually cheaper than their managed fund counterparts, this development is likely to be a positive for share market investors.

This article was written by Paul Benson.

Paul Benson can be found on the podcast Financial Autonomy, and is a regular contributor to Fairfax.